The Context

Censorship has been a tool for controlling information and suppressing dissent throughout history. It is often employed by authoritarian regimes to maintain power and control over their populations. The roots of censorship can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where rulers sought to suppress dissenting voices and control the narrative surrounding their reigns, through to recent history and the modern day:

- Ancient Rome: Emperor Augustus, who reigned from 27 BCE to 14 CE, implemented strict controls over literature to promote his image.1 From around 29 BC "the explosion in the number of Augustan portraits attests a concerted propaganda campaign aimed at dominating all aspects of civil, religious, economic and military life with Augustus's person."2

- Middle Ages: The Catholic Church worked to suppress novel ideas, including heliocentrism, by banning books and punishing dissenters.3 The first Index Librorum Prohibitorum was published in 1559 by the Sacred Congregation of the Roman Inquisition.4 The final index was published in 1948. While it was abolished in 1966, the official gazette of the Holy See published, from Pope Paul VI, that the index "retains its moral force despite its dissolution".

The master title page of Index Librorum Prohibitorum (in Venice, 1564). Credit: Wikipedia.

- Russian Empire: Censorship was systematically developed by the tsars late in the eighteenth century, partly as a frightened response to the excesses of the French Revolution. From 1976 the government set up censorship committees to determine which foreign books may be allowed to enter the country.5

- Nazi Germany: The Nazi party used extreme measures to control information, including media monopolisation. During the first weeks of 1933, the Nazi regime deployed the radio, press, and newsreels to stoke fears of a pending "Communist uprising". By 1944, the newspapers that remained operated in strict compliance with government press laws and published material only in accordance with directives issued by the Ministry of Propaganda.6

- Arab Spring: During the Arab Spring, from 2010 to 2012, governments across the Middle East employed extensive censorship measures to suppress dissent and control the narrative surrounding protests.7 For instance, the Egyptian government initially blocked access to social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, and later cut off all internet access nationwide to stifle communication among protesters.8

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is dedicated to measuring internet censorship and promoting transparency in online communications. Their 2024 report on Russia9 highlights the systematic suppression of independent media between September 2023 and September 2024. Key findings indicate a significant increase in censorship efforts, including widespread blocking of news websites and the restriction of access to independent journalism, reflecting a growing trend of media control aimed at stifling dissent and limiting public discourse.

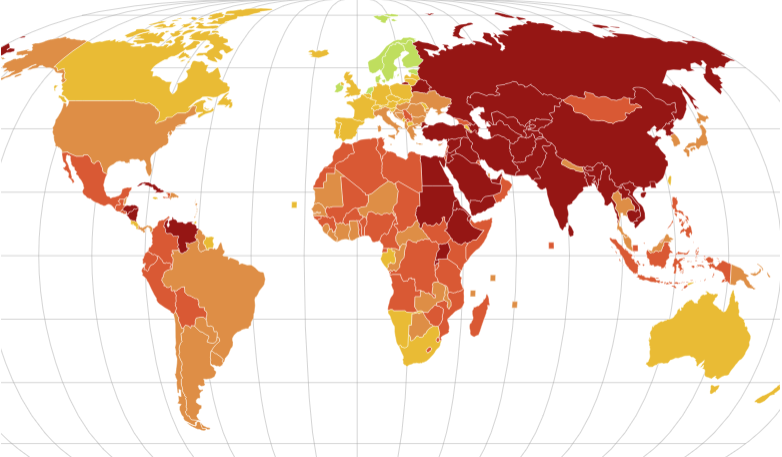

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is an organization focused on defending press freedom globally. The 2025 World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) indicates that economic fragility has emerged as the primary threat to press freedom, affecting numerous countries.10 The report highlights a significant increase in censorship and violence against journalists, particularly in regions facing economic instability, which has further compromised the ability of the media to operate independently and effectively.

In 2025, the conditions for journalism are poor in half the world’s countries. Credit: Reporters Without Borders.

Footnotes

-

Rudich, V. (2006). Navigating the Uncertain: Literature and Censorship in the Early Roman Empire. Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, 14(1), 7–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29737288 ↩

-

Walker, S., & Burnett, A. (1981). The image of Augustus. British Museum Publications. ISBN 978-0-7141-1270-1. ↩

-

Fabio Blasutto, David de la Croix, Catholic Censorship and the Demise of Knowledge Production in Early Modern Italy, The Economic Journal, Volume 133, Issue 656, November 2023, Pages 2899–2924, https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/uead053 ↩

-

Brown, H. F. (1907). Studies in the history of Venice (p. 70). New York, NY: E.P. Dutton and Company. ↩

-

Rogers, A. R. (1973). Censorship and Libraries in the Soviet Union. Journal of Library History, Philosophy, and Comparative Librarianship, 8(1), 22–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25540391 ↩

-

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "The Press in the Third Reich". https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-press-in-the-third-reich. Accessed on 19th May 2025. ↩

-

Al Jazeera. (2021, January 27). The social media myth about the Arab Spring. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/1/27/the-social-media-myth-about-the-arab-spring. Accessed 19th May 2025. ↩

-

Time for the People. (2020, December 17). What happened to the internet since the Arab Spring? https://timep.org/2020/12/17/from-free-space-to-a-tool-of-oppression-what-happened-to-the-internet-since-the-arab-spring/. Accessed 19th May 2025. ↩

-

Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2024). The systematic suppression of independent media in Russia. https://ooni.org/post/2024-russia-report/. Accessed on 19th May 2025. ↩

-

Reporters Without Borders. (2025). RSF World Press Freedom Index 2025: Economic fragility a leading threat to press freedom. https://rsf.org/en/rsf-world-press-freedom-index-2025-economic-fragility-leading-threat-press-freedom. Accessed 19th May 2025. ↩